These are the two Anglo model concertinas played by Sergeant Herbert John Chudleigh, 1 Australian Field Ambulance, AIF.

Chudleigh from Ashfield, NSW, was 22 years old when he enlisted at Sydney in 1914, and noted his occupation as 'storekeeper'. However, his Service Record contains a letter from his pre-war employer, noting him as an accountant with the New South Wales Government Railways & Tramways Chief Accountant's Office. After initial training, Chudleigh embarked for overseas service aboard the transport HMAT Euripides, travelling with the first Contingent Convoy to Alexandria. After further training, Private Chudleigh landed at Anzac Cove within the first 48 hours of the beginning of the Gallipoli campaign.

After the Gallipoli evacuation 1 FAmb was moved to France via Marseilles aboard the transport Simla. As casualties rose amongst his unit, Chudleigh was promoted through the ranks and by May 1917, Chudleigh was a Sergeant.

At the end of the war, as a 1914 enlistee, Sergeant Chudleigh was granted early leave and returned to Australia in December 1918. He was discharged from service on 24 February 1919.

This concertina is the first of two used by Sergeant Chudleigh on active service. The first, he related in his letter of offer to the Australian War Memorial of 1924, 'I took away with me to the war and carried with me until August 1916'. At Mena Camp in Egypt prior to the Gallipoli landings, 'I used to play it, at the head of the column on the march, also, I played it at several church parades (where at times we had no other music) and also at various concerts etc in Egypt and France. I also took it with me at Anzac, where we managed to knock out some fun in the dug outs, during an impromptu concert or sing-song. It accompanied me also to Cape Helles when a section of my unit were sent there and once I thought I had lost it [while there] when our dug out was blown up by a shell. Fortunately I managed to dig it out, all covered with dirt, but still able to get a tune out of it.'

'When we went to France, I still carried the old concertina until about August 1916 when I decided to pension the old instrument off and I sent it back home. I had it autographed by the officers and men of the unit, and also marked the names of the different places where I carried [it].'

'The boys of the unit were so used to the old instrument that they made a collection and gave me the money to buy a new concertina, which I had sent from London and which I carried with me and used to good purpose till I left the unit.'

The second concertina was an upgrade for Chudleigh, sporting an extra six keys and costing £3 13, as opposed to his first example, which retailed for a pound less.

Both concertinas are displayed in Australian War Memorial Museum.

By Betsy Sandbach and Geraldine Edge

Page 115

Note: During the second world war some children, often orphans from the bombing of English cities, were sent to the colonies for their safety and hopefully a better future. This story is the result of their ship being sunk by a German raider and the survivors rescued by the German crew. They were on their way to safety when one of the young female escorts died on board.

" Miss Herbert Jones took upon herself the task of accompanying children, through the dangers of war at sea, from England to New Zealand, a measure which it is not for us to pass judgment on here. For her this meant consciously taking the dangers and sacrifices upon herself which war at sea brings with it. I believe that all sailors on board, whether friend or foe, realise that the laws of the sea are hard in themselves, and that war at sea, our element, is inexorable and demands great sacrifices.

When this harangue came to an end, a Church of England chaplain, once an escort, and now a fellow-prisoner, stepped forward and was allowed to say a few words and a prayer.

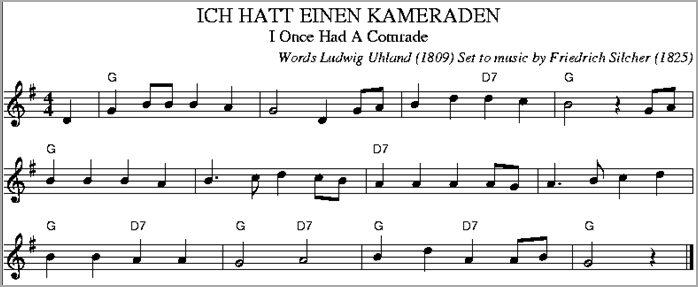

Then the German Military March "Ich hatt einen Kameraden" was played by pipe and concertina as the body of the girl escort was lowered into the fathomless depths of the Pacific, the loneliest ocean in the world."

Note on Ich hatt einen Kameraden:

One of the most popular German folksongs, written during the Napoleonic wars (1809). Words by Ludwig Uhland, poet, historian, and professor of German literature at the University of Tübingen in his home town. The poem was inspired by the Tyrolian freedom fighters and their struggle against Napoleon. Sixteen years later, the university's music director, Friedrich Silcher, dusted off a 3/4 time folk melody, "Ein schwarzbraunes Mädchen hat ein'n Feldjäger lieb" (which he considered to be of Swiss origin), changed it to a 4/4 marching tempo, and fitted Uhland's words to it. The song, included in his Folksongs, 1827, has been a favorite ever since. It is often performed in memory of the veterans of the two world wars and for the German veterans day observance on the third Sunday in November.

Translation of the Words

1. I had one faithful comrade

'Ere we heard the trumpet's call,

And we pledged our hearts forever

In battle joined together

|: To beat the foe or fall. :|

2. A musket shot came screaming

To seal his fate or mine

Right at my feet he stumbled,

And friendship's shrine it crumbled

|: Around that friend of mine. :|

3. His hand is blindly seeking

The clasp I cannot give

For duty calls me onward

Farewell my dying comrade,

|: Our love shall ever live. :|

Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 - 1916), Thursday 8 April 1897,

TELEGRAPHIC NEWS. PERTH, March 31. City Police Court to-day.

A peculiar accident happened at Albany to-day. The S.S. Cloncurry arrived from the eastern colonies, and one of her passengers, who had been on shore, was proceeding down to the jetty to rejoin the ship. He was playing a concertina, and was apparently so absorbed in the music that he walked over the end of the pier into the sea. After a little while he managed to scramble on to the piles at the jetty, and so was rescued.

One of the most fondest of my early recollections stems from the fact that my mother was an accomplished musician – particularly on the concertina and the Irish Pipes. She was the proud possessor of the most beautiful concertina I have ever seen. How she came by it I don’t know. Perhaps it was a wedding present, or perhaps purchased in her pre-nuptial days when her financial resources were at a peak period of affluence. It was a lady's model, with a wonderful tone, beautifully made, and the two ends were of polished maple with ivory keys, and ornamented with a spray of ivy leaves, inlaid in an intricate design, and the bellows were richly decorated.

I can distinctly remember, how, on summer evenings she would treat us to an impromptu concert by playing and singing old Irish songs, such as “Mother Macree” and “Killarney “; sung with just the correct Irish accent and native interpretations, while we sat around in rapt attention. It is safe to say that, I knew the words of “Killarney “ and “The Irish Lullaby “ , as soon as I knew “The Lord’s Prayer “. These entertainments usually began with a few musical chords as her fingers ranged tentatively over the keys of her beloved instrument, first to become familiar with the touch. As her time was limited after caring for a young family, these recitals were only occasional, and we awaited them with interest. After a brief introduction, as soon as her toilworn fingers became familiar with the keys, she would play a medley of Irish airs, delicately blended with a ripple of grace notes so skilfully played that the changeover from one tune to another was almost imperceptible, and the various tunes became integrated. Then she would break off into an Irish jig which would set our toes tingling and our feet stamping, beating out the tune. Then, just to show there was no partisan feeling in her music she would couple “The Battle of the Boyne Water” with the “Wearing of the Green” in a grand finale.

In later life I have had the pleasure of hearing many professional exponents of the concertina, but never have I heard one played with such grace and musical ability as that displayed by my mother. She usually stood when playing and with a gentle swaying of the body from side to side, would lend an added rhythm to the tune – weaving the instrument over her head in a circular motion, to complete the recital as she began, with a series of long drawn musical chords.

This was usually a sign for the younger members of the family to troop off to their little trundle-beds and kneel down dutifully on the hamper mat and lisp the well-remembered prayers of our childhood – who could forget them? There were no churches or Sunday schools in those early pioneering days, and all religious instruction had to begin at home; and after my mother’s death, my father would gather the family around him each Sunday night and read a chapter from the Bible and explain it to us to the best of his ability. What a pity this old family custom has been allowed to die out! It has proved a sheet-anchor to many a young person starting out on life’s tempestuous sea.

How strange it is that we never appreciate fully, the gifts at hand until it is too late. After the death of my mother, her beautiful instrument was just a toy, neglected and allowed to deteriorate, until now it’s just another memory. We were too young at the time to appreciate its sentimental value; but I would gladly give twenty dollars today for just one ornamented end of the instrument which gave us such pleasure, and which was really “a thing of beauty and a joy forever “.